The Sose Bay area on the Danish island of Bornholm is a beautiful place. Here, the lush greens of the partly forested coastline with its white sandy beaches meets the Baltic Sea, and at the horizon there is nothing but sky.

Sose Bay in October 2013 (Photo: Lars Henrik Nielsen, GEUS)

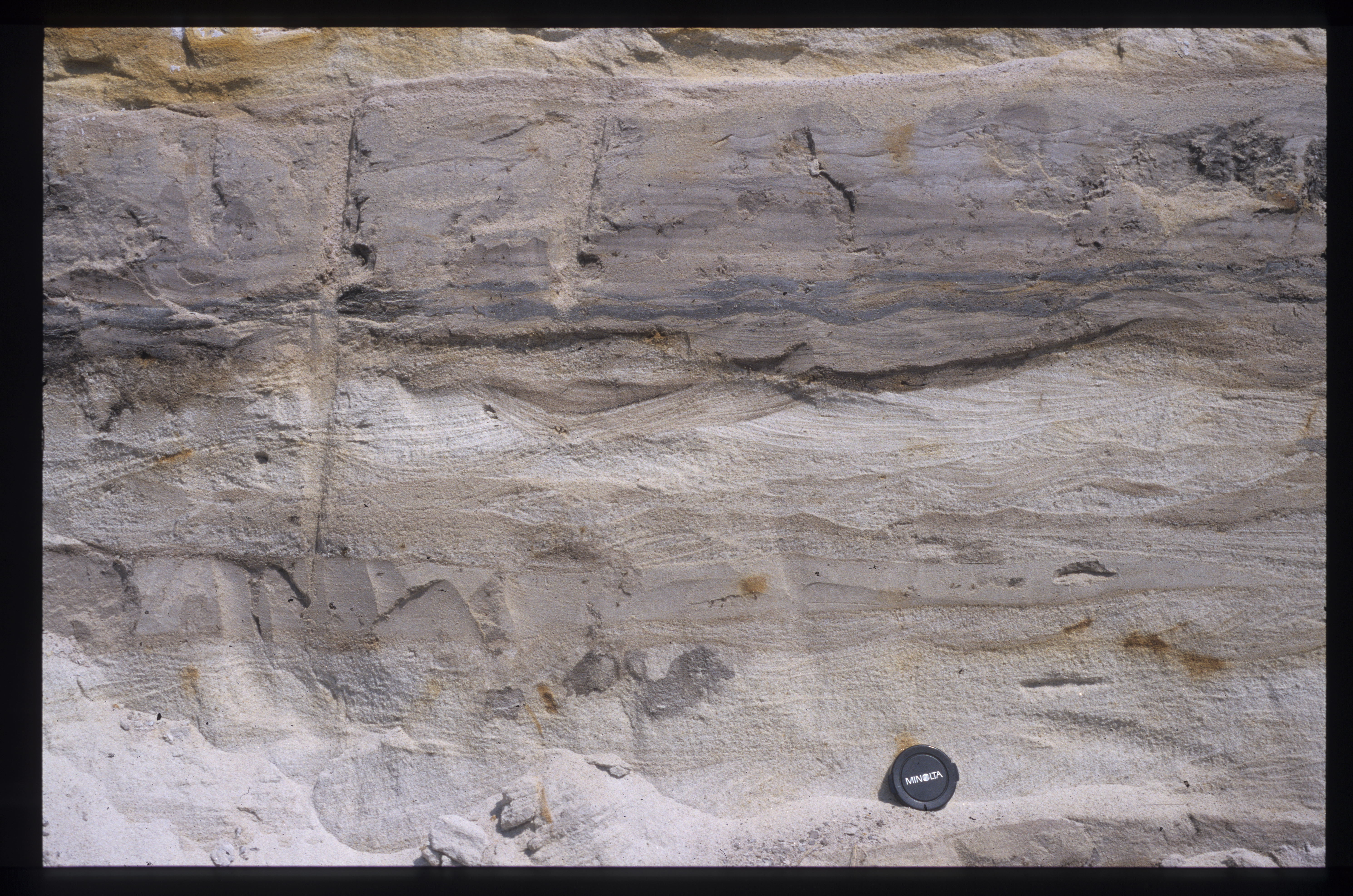

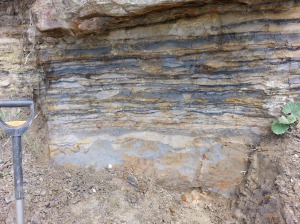

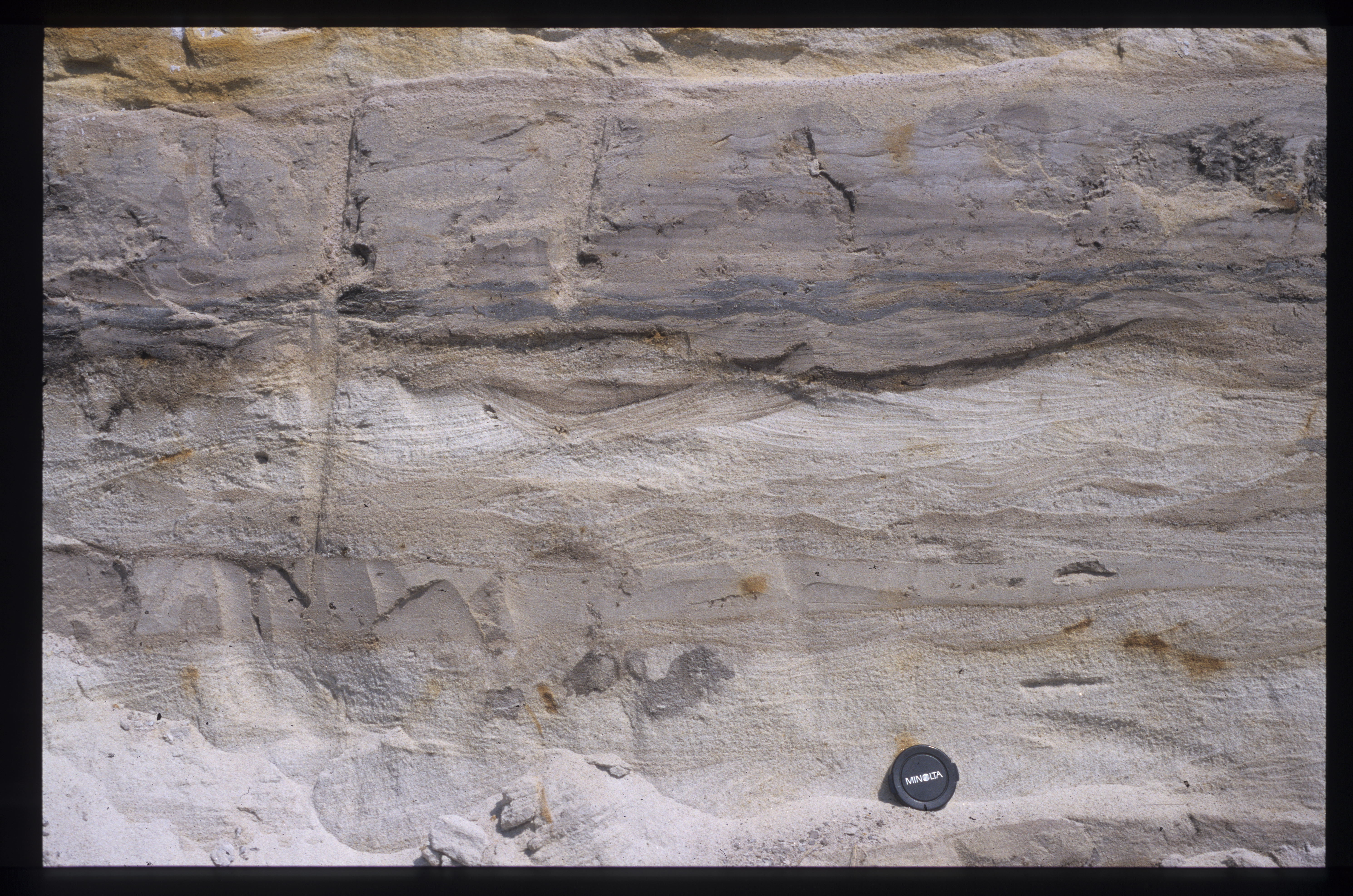

Early Jurassic rocks crop out along the coast; the sands and clays still soft after 200 million years, revealing a multitude of sedimentary structures when scraped free of their weathered surfaces.

Left: a small weathered coastal section. Right: Same section after rinsing. (Photo: Sofie Lindström, GEUS)

Wave ripples (Photo: Gunver K. Pedersen, GEUS)

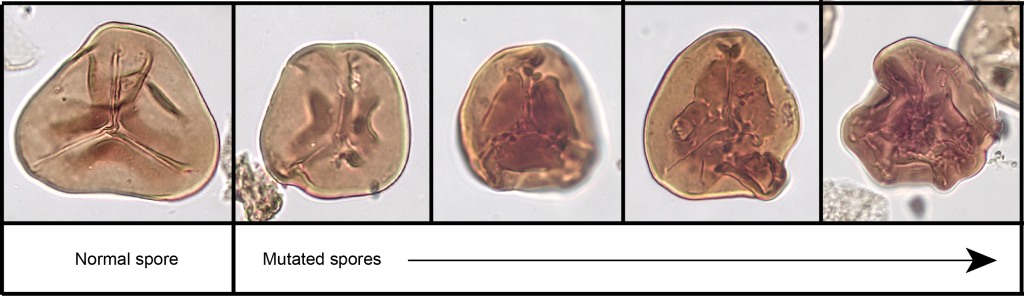

The most continuous sedimentary succession in the coastal cliff is exposed east of Sose Odde. It comprises a c. 24 m thick section including restricted marine, eustarine, lacustrine and fluvial deposits, and was described in detail by Surlyk et al. (1995). The outcropping succession belongs to the Sose Bugt Member of the Rønne Formation, which was assigned a Hettangian–Sinemurian (Early Jurassic) age based on its fossil palynological (spores, pollen, microalgae) content. In 2014, Clemmensen et al. described the presence of steep-walled, flat- to concave-bottomed depressions, with a raised ridge at each side, that were interpreted as dinosaur tracks.

One of the dinosaur tracks described by Clemmensen et al. (2014). (Phoyo: Sofie Lindström, GEUS)

The dinosaur tracks are found in layers interpreted to have been deposited in small streams on a large coastal plain. Clemmensen et al. (2014) suggest that the dinosaurs may have preferred to use shallow channels as paths. The succession also contains thin coal seams and layers penetrated by numerous vertical roots, remnants of 200 million year old vegetation.

Numerous thin vertical roots penetrating a thick sand layer (Photo: Sofie Lindström, GEUS).

So these are the sediments that lie immediately beneath our feet when we walk the fields at Sose Bay, below a thin cover of Quaternary sediments. But what lies beneath? Would sediments deposited before, during and after the end-Triassic mass extinction be present?

The drill site and equipment (Photo: Gunver K. Pedersen, GEUS).

In order to find out, we performed a core drilling in the Sose Bay area, with the aim to reach typical red and green coloured Late Triassic sediments – and hopefully Triassic–Jurassic boundary sediments.We drilled with a core drilling technique that sealed the sedimentary cores in plastic pipes.

The core catcher brings up a new core (Photo: Gunver K- Pedersen, GEUS).

John Boserup checkes the bottom of a core (Photo: Gunver K. Pedersen, GEUS).

By checking the bottom of each pipe when they were brought to the surface, it was possible to see when the red and green Triassic had been reached. At a depth of 110 m below ground, we reached red Triassic sediments.

Red and green clay and some sand at the bottom of a core (Photo: Gunver K. Pedersen, GEUS).

But because the cores were sealed in red plastic pipes, we still had no idea how complete the drilled succession would be. All we could do was wait until the cores had been transported back to GEUS.

Sealed red plastic pipes containing the cored succession of the Sose-1 well (Photo: Gunver K. Pedersen, GEUS).

To be continued…